By JAMES WALLIS

The recently released film ‘1917’, directed by Sir Sam Mendes, has attracted a wealth of public, media and industry critical acclaim, both across the UK and internationally. As someone interested in cultural representations and portrayals of the conflict, I was excited to see how this re-imagining of the First World War might go some way to retaining, maybe even reviving some of the widespread popular interest in the conflict garnered over the period of its recent centenary commemorations.

I saw the film at my local cinema, an 8pm post-work Friday packed house. Audience buzz suggested high levels of expectation at the promise of an enticing evening’s entertainment. Sadly it is hard to avoid film trailers and online commentary these days, so the unavoidable advertising promotion I encountered at Waterloo station, alongside numerous discussion pieces, tweets and newspaper reviews, meant my expectations were two-fold; firstly that the film had a ‘Saving Private Ryan’-style (surprisingly simple) connotation of two youthful-looking soldiers needing to deliver a crucial message in order to prevent a doomed attack, facing nigh-on impossible odds in a high-stakes race against time set within a brutally harrowing theatre of conflict. Secondly the film utilised the novel concept of a single continuous camera shot throughout its entirety. This process of long takes and editing at a bare minimum would deliver an illusion of one continuous movement, as a way of telling the leading pair’s gripping story. Keeping spoilers to a minimum, the title of another famous post-war play by R.C. Sherriff – most recently portrayed as a 2018 filmed production – ‘Journey’s End’ could hardly be a more apt description of the final sense of release at seeing the film’s credits roll.

The spectacle, tension and drama conveyed by these two filmic frameworks makes for a very watchable, even bewildering viewer experience. Its visceral, immersive and sensory nature works especially well in cinema format. One striking thing is that the film quickly goes against the notion of static trench warfare, by taking the two principal characters, Blake and Schofield, out into and through the iconic space of ‘No Man’s Land’, then German trenches and beyond. Though I gather some viewers have encountered forms of motion sickness, the fast-pace panning of the camera does give a constant sense of movement, spatial progress in always moving forward – at times perhaps a tad contrived, but an empathetic, effective device for delivering a story filled with physicality, action and chase sequences. The real-time effect plays out proceedings as a metaphorical step-by-step journey of peril, one that the viewer can never leave, so must endure alongside the characters. Endless exteriors, bright vistas and open spaces grant a contrasting claustrophobia to the confined trench networks, and various indoor or underground locations (the subterranean tunnel scenes evoke the intensity of Sebastian Faulks’ 1993 novel Birdsong). Set-pieces dotted through-out also prove impressive visual spectacles, particularly the cinematography, choreography, production, lighting, and a host of other technical aspects I’m under-qualified to muse on. One couldn’t help but notice the incredible sense of realism within this recreated environment – as historian Chris Kempshall has observed, First World War virtual reality as depicted in creations such as ‘Battlefield 1’, are now important influences in how we visualise the spaces of the conflict (as well as being functional tools for learning). The cinematic viewer experience felt very much like a first-person game environment, a brief moment in time hurtling through these eerie environments.

Ironically it is this factor of high-calibre stylistic recreation that brought my thoughts to my doctorate research conducted at the Imperial War Museum (IWM). The IWM played a role as a repository for some of the film’s source material and inspiration, as various recent in-house promotional videos have shown. During the build up to the film’s release, there was also a wave of discontent amongst some First World War historians about a remark made by the film’s writer, Krysty Wilson-Cairns; ‘I couldn’t research online: I had to go the Imperial War Museum and to France, and find books out of print for decades’ (tweet by Dr Kyle Falcon, 5th January 2020). The revelation prompted a lot of ensuing threads and conversations in historical circles – namely around the apparent neglect of new research and written material generated by the conflict’s centenary, but further extending out into discussions around authenticity and accuracy, using archival sources online, the role of historians within the film industry and so forth. Airing the merits or otherwise of these fall beyond the scope of this piece, but one IWM influence that felt overly apparent to me (especially during the film’s initial phase) was in comparing the film as a cinematic walkthrough of the IWM’s 1990 ‘Trench Experience’. Here we have a similar, very literal progression through the experience of the Western Front, with heightened sensory encounters of sound, sight and touch drawing visitors into aspects of its multifarious horrors, gore and brutality. Of course, those who passed through this low-lit walk-through space were detached, knowing that this was a fake recreation – but perhaps also allowing their imaginations to conjure up mental recreations amidst the fixed plastic mannequins and growling rumble of artillery fire. And whilst the recreated trench display had significantly less budget or contemporary technology to draw upon, the parallel between these two portrayals is the persistent public desire to know and understand what the War ‘must have been like’. Along with the partnering ‘Blitz Experience’, this IWM installation proved one of the most popular and memorable for its visitors – revealing the willingness of audiences, both of thirty years ago and now, to immerse themselves in iconic, precise yet somehow surreal recreations of the past.

What ‘1917’ also does is to build upon the technical skill, craftsmanship and wizardry of Peter Jackson’s ‘They Shall Not Grow Old’ film, released in the autumn of 2018. It was a portrayal of the conflict that did much to colourise, and moreover individualise or humanise, how we understand the First World War post its centenary. As audiences, we remain profoundly moved in and affected by watching powerful accounts and versions of historical events, sitting as they do as contradictions in their incredible familiarity and ultimate unknowability. Thus the orchestrated sequences of feature films place us as viewers in the position of these soldiers, discovering and briefly inhabiting (almost theatrical) sets of trenches, mud, blood and corpses, as events progress through the horrors of violence, carnage and destruction of the War years. Whilst there are passing reference to the more common First World War clichés of futility and ‘Lions led by Donkeys’, the emphasis of ‘1917’ is much more on the haunting nature of quite literally fighting through this landscape, and subsequently on the concept of (albeit naïve) duty and devotion, as opposed to outright disillusionment. That said, evocative tracking shots through trench lines filled with static soldiers induces ideas of Stanley Kubrick’s 1957 film ‘Paths of Glory’, prompting typical war film motifs around fear, trauma, and dark humour. One of ‘1917’s’ contemporary tributes – the desperately tense tracking sequence of one of the main characters running across waves of attacking soldiers going over the top, amidst heavy explosions of shellfire – is both thrilling and terrifying to watch.

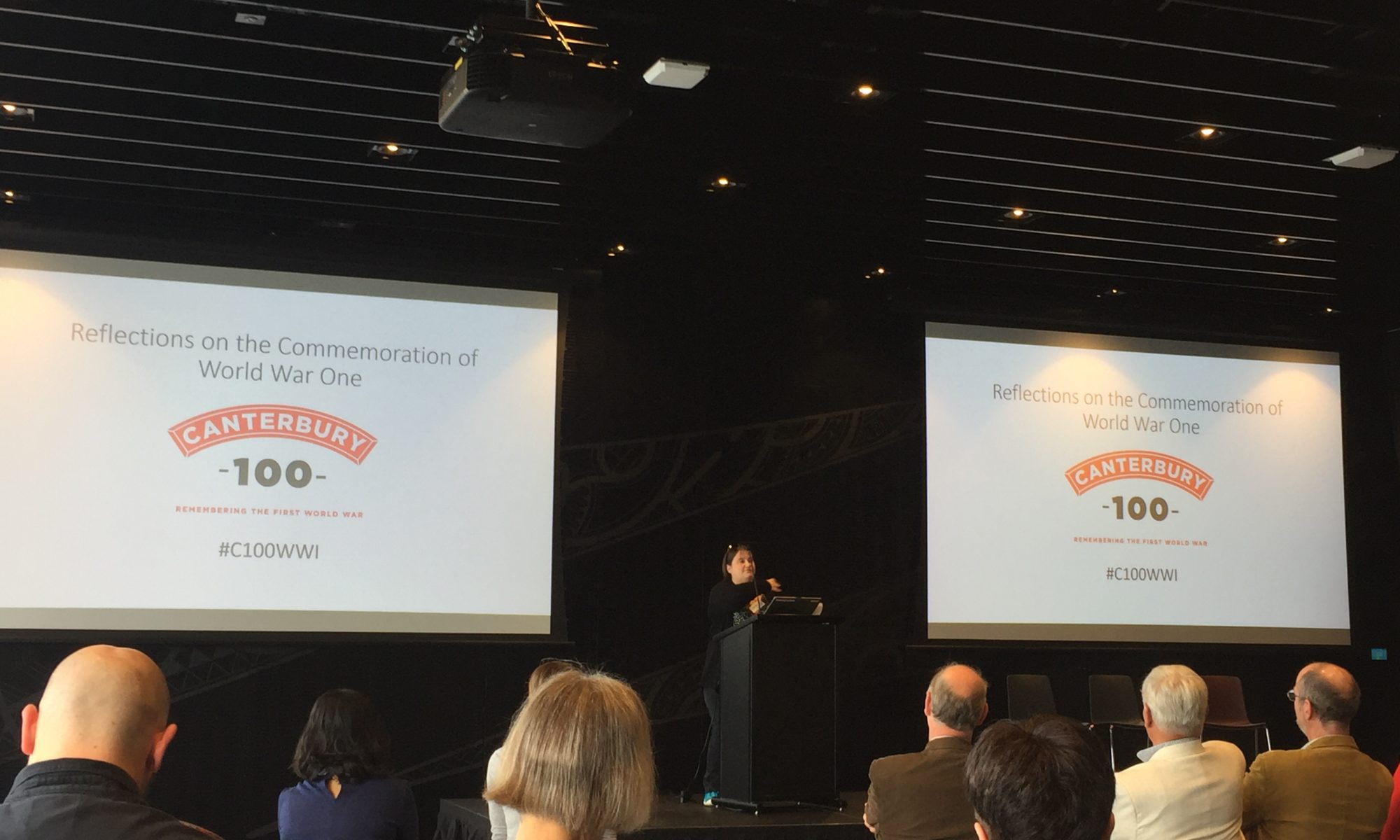

‘1917’ should ultimately be judged – and recommended – as a piece of high-quality entertainment. The fact that most of the iconic big-screen portrayals of the First World War (namely ‘All Quiet on the Western Front’, 1930) date from the immediate post-war period, speaks volumes about the challenges of conveying or recreating the brutally raw intensity of what soldiers experienced and endured on its battlefields. Though unlikely to satisfy historical purists, ‘1917’ nevertheless portrays the First World War in a vividly powerful way, so warrants consideration within the context of Britain’s recent cultural memory of the conflict. On the one hand, the film has come at an opportune time for a country that dedicated so much local, regional and national effort to its recent commemoration. But equally, one year on from all that focus on remembrance – with new ideas of aestheticised artistic installations, local history projects and creative commemoration – what the broader British public now wishes to take in is a more graphic, gritty and contemporary portrayal that shows to remind us about what we already knew about the conflict (with a nod to the role played by troops from across the British Empire). Online reviews are already pitching the idea of viewing the film as an act of witnessing, which as Ross Wilson has previously argued, instigates continued appreciation of sacrifice, heroism and remembrance (on an individual and national level). The ‘Reflections on the Centenary’ project team will publish on the meaning and significance of some of these notions around the conflict’s centenary commemorations, in our final project report due at the end of this year.